From the book Methods of Modern Sculptors by Ronald D Young & Robert A. Fennell

Recent scholarship has traced bronze work back at least to 5000 B.C. and to cultures from the Mediterranean to China. However, the purposeful fusing of metals into alloys goes back to about 1800 B.C. Bronze is basically an alloy of copper and tin but almost all bronze is improved in fusibility with the addition of zinc and lead, and many other elements may be added or be present naturally in small amounts.

The Egyptians were the earliest known miners of copper. Their main source was the island of Cyprus, from the which the word copper is derived. The Phoenicians were great seafarers with access to the copper of Cyprus, Arabia and other lands, to the tin of Britain, and to both these metals and zinc and lead from Spain. They became skilled workers in bronze and carried their craft to many other countries. They also unfortunately contributed to the destruction of some early and great bronze art, for bronze was always in demand for the manufacture of weapons.

To produce a bronze casting, metal has to be brought to about 1700 F or more and poured into some kind of mold which provides the negative image of the work. They early molds were intaglio, that is, cut into stone or other hard material. Another early method used sand and clay, bonded together by oil, into which the original piece was pressed, then the cavity filled with molten metal.

The most accurate and still the most popular method of casting bronze is the cire perdu or lost wax technique. It was known in Egypt by about 1570 B.C., may also have developed in China a few decades later, and by the 7th century B.C., had been brought to a high level by the Greeks. In essence, the original model is sculpted in wax, then covered by some sort of heat resistant material, then heated to the point where the wax melts out, leaving the negative impression inside the mold to be filled with molten metal.

The earliest bronze castings were solid and their weight, as well as the size of the heat resistant crucibles that could be handled, limited the size of the casting. Large statues and vessels were cast in sections and then joined with rivets or soldering, both crafts that the Greeks perfected some 3000 years ago. By the 6th century B.C., Greek artists and foundrymen had developed assembly line methods to satisfy the demand for their products in many lands. By the 4th century, the Romans had similar methods for producing armor and weapons for their legions.

The Greeks also developed the basic method for making many copies of a work. The original was sculpted in a hard material such as stone or wood and then a mold was formed in sections over it. The "piece mold" was then removed from the original, a layer of wax was poured into the reassembled mold, and the core was filled with refractory material, after which the wax was melted out.

A great breakthrough came with hollow core casting, requiring far less metal than a solid casting. Here, instead of the original being made in solid wax, the wax was modeled over a core of refractory material and the mold was formed over the wax. With the core material held in position by bronze pins, the wax was melted out and the bronze poured into the space between the core and the mold, both of which could then be chiseled away once the bronze had cooled.

In the many centuries from the birth of Christ to the Renaissance, art in bronze flourished mainly in China and especially India, where dancers and other humans figures were skillfully depicted in motion and the sculptures elaborately decorated with engraving and inlays of precious metals and stones.

With the Renaissance, Florence and then Venice attracted the greatest sculptors. Donatello of the famous David bronze and Ghiberti, both trained in the Guild of Goldsmiths, were followed in Florence by Giovanni, Michelangelo, Riccio, Bologna, and Cellini. The Memoirs of Cellini give fascinating accounts of the art and craft of bronze casting.

In Germany, foundries developed techniques for casting huge bells and cannons weighting thousands of pounds in a single pour. The ability spread to France where, during the 17th century, cannon foundries cast large statues, especially equestrian figures, in just one or a few pours. Although the 18th century saw much bronze work of household size, in the form of clock cases, candelabras, and the like, Falconet's colossal bronze of Peter the Great was cast in one pour - all 16 tons of it.

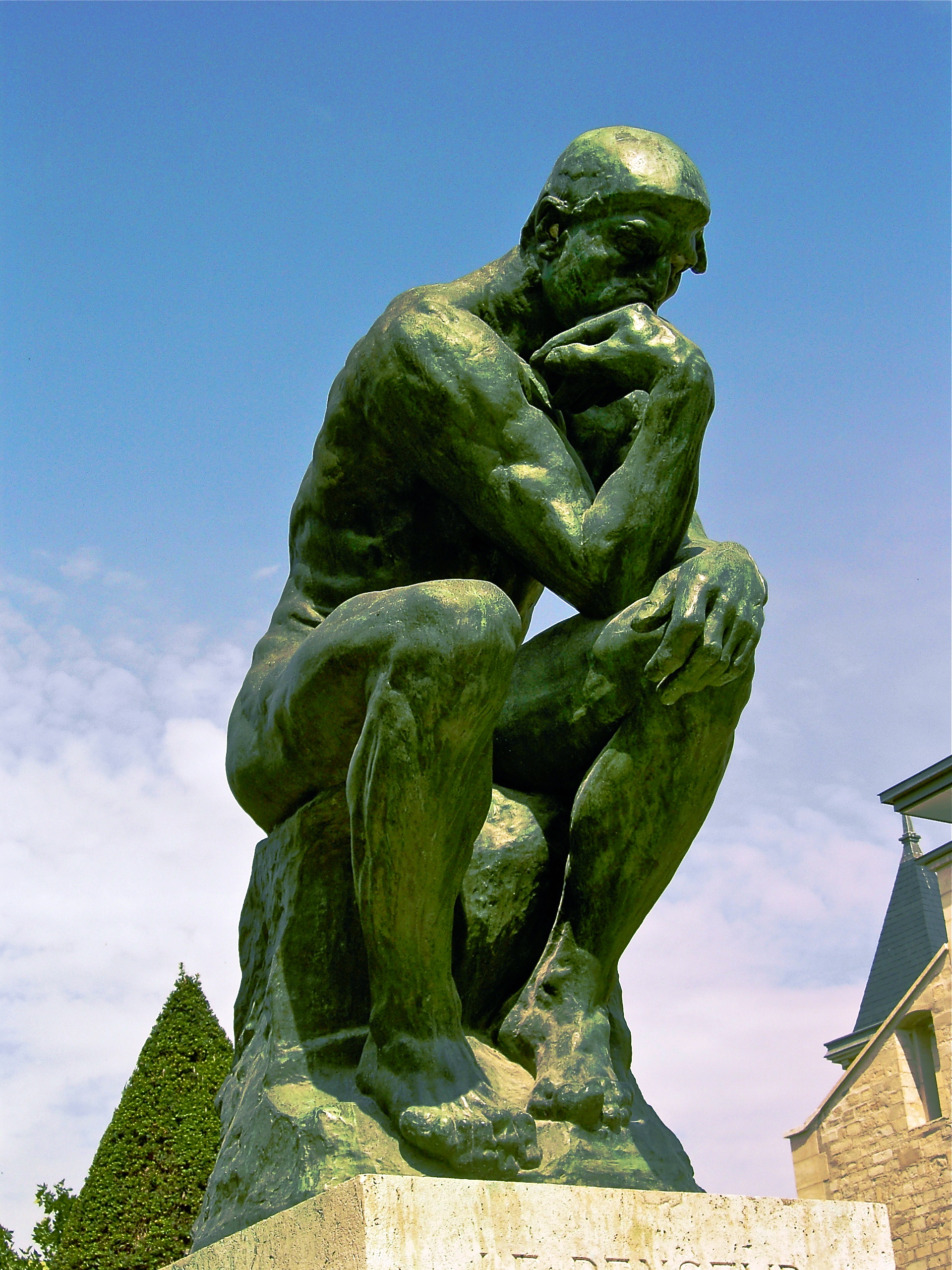

In the 18th century, Barye was one of the first great artists to break away from traditional styles, with beautifully finished bronze sculptures of animals. Then came Rodin (1840-1917), one of the greatest sculptors of all time, who used living models for his masterly anatomical recreation: when his male nude, The Age of Bronze, was shown, he was accused of casting from life, that is, actually molding a living person.

Pictures: "David, Donatello" by Patrick A Rodgers/ "The Thinker, Rodin" by Andrew Horne